Charlotte Metcalf is the Editor of Great British Brands and the co-presenter of Break Out Culture, a weekly podcast with former Minister of Culture, Lord Vaizey. She is also a film-maker, author and journalist. She reports regularly for Thomas Lyte on cultural events, exhibitions, fairs and publications that are of interest to the communities of craftsmen we represent and celebrate, with a particular focus on goldsmiths and silversmiths.

.. … .. … .. … .. … .. … .. … .. … ..

As we explore the Buckingham Palace exhibition, discover how 18th-century gold and silversmiths defined an age of glorious Georgian style

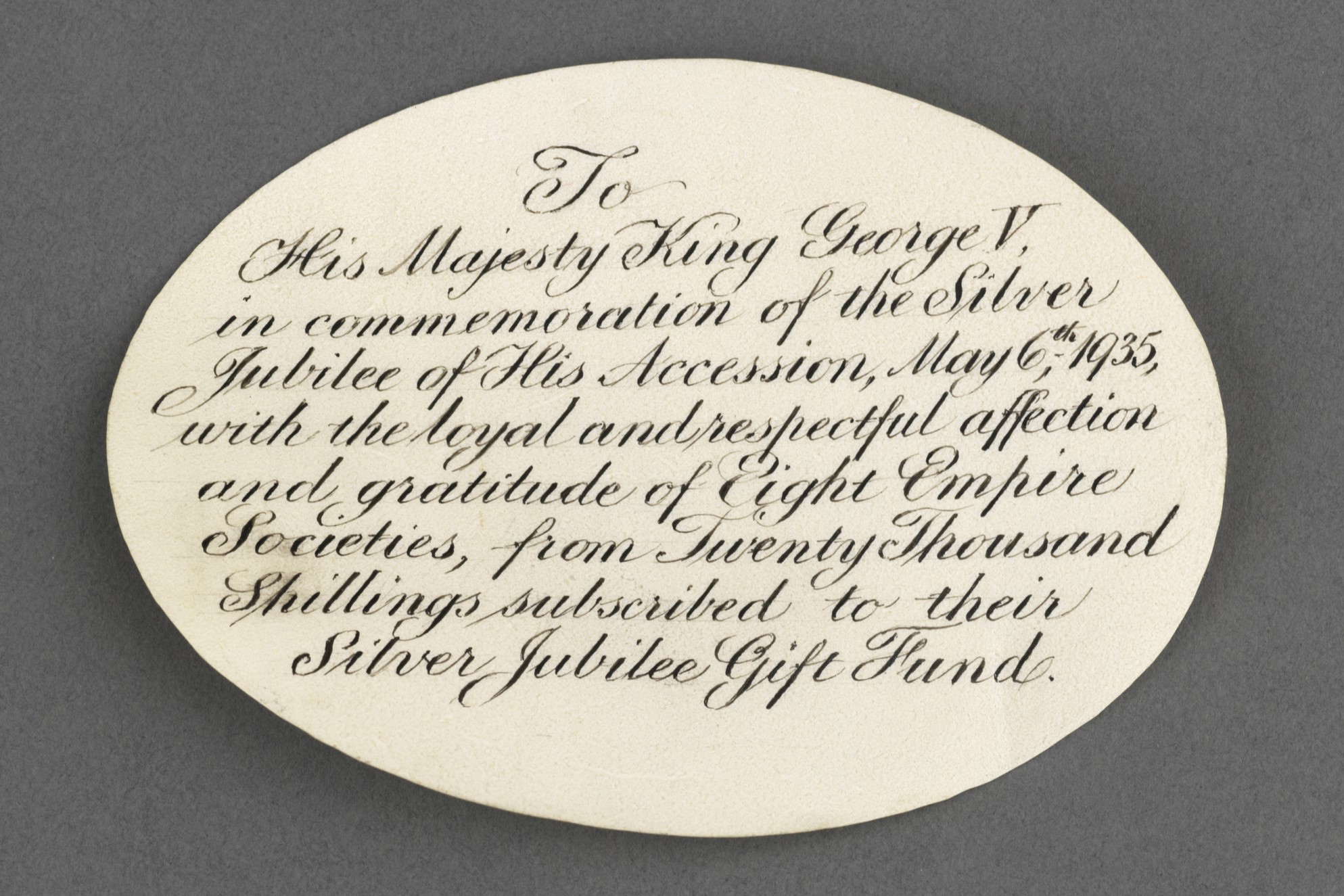

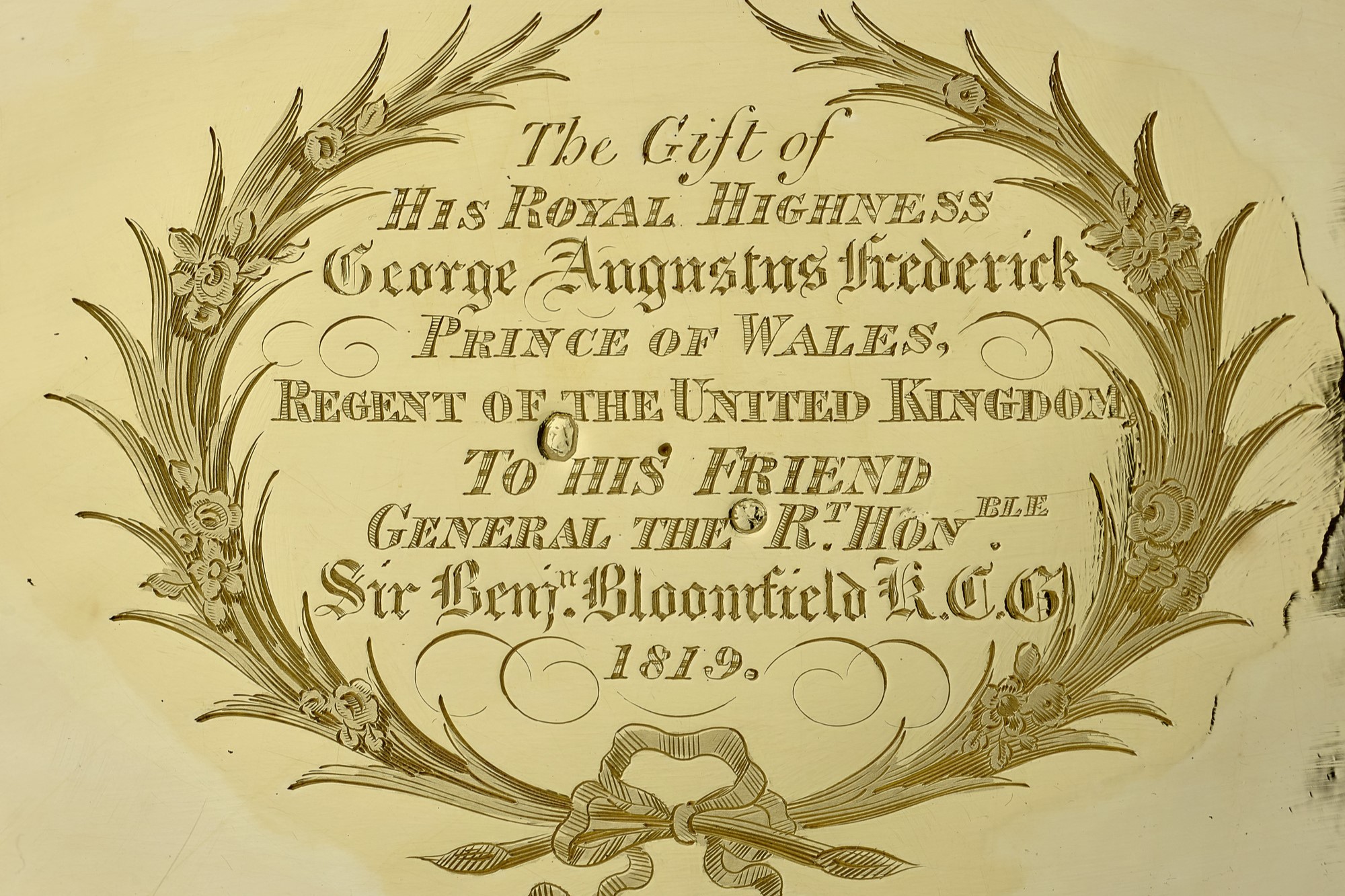

There is still time to catch Style & Society: Dressing the Georgians at the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace. While many have flocked there to ogle the lavish gowns, towering powdered wigs and ornate buckled shoes, anyone interested in craft will be fascinated by the smaller treasures on display.

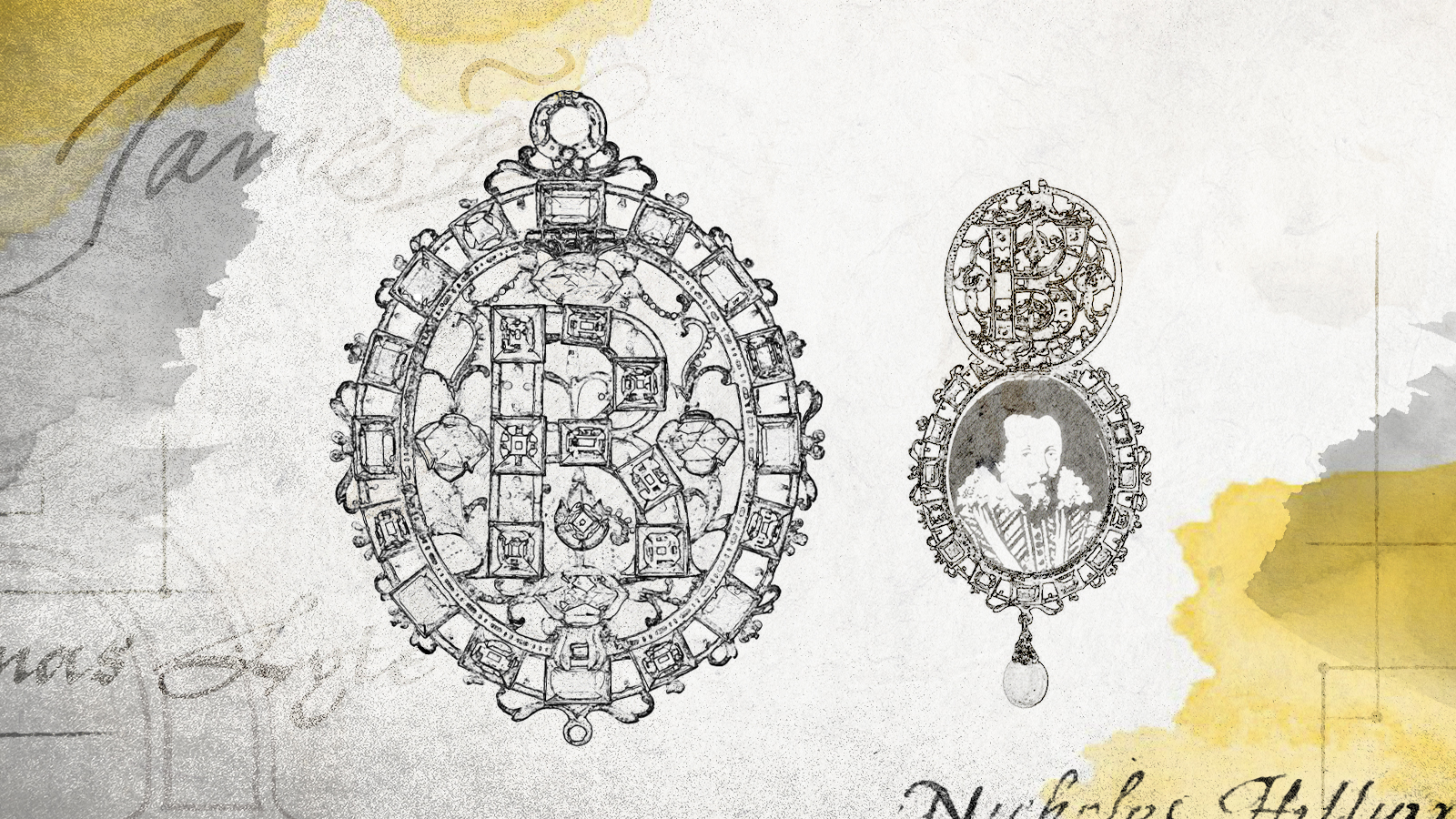

There is Queen Charlotte’s ring, given to her on her wedding day by her husband George III. It’s set with a miniature of her husband beneath a large flat-cut diamond, surrounded by smaller ones. Thought the jeweller is unknown, the portrait is by Jeremiah Meyer, a German-born miniature painter who came to England in 1749.

![Slawn x Cup Culture FA Cup trophy made by Thomas Lyte]() SLAWN x Cup Culture: Where Football Meets Design, Art and Craft

SLAWN x Cup Culture: Where Football Meets Design, Art and Craft![Designers Makers Of The Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Processional Cross 3 1306x1800]() Culture Round-Up: 2022 and the Queen Elizabeth II Processional Cross

Culture Round-Up: 2022 and the Queen Elizabeth II Processional Cross