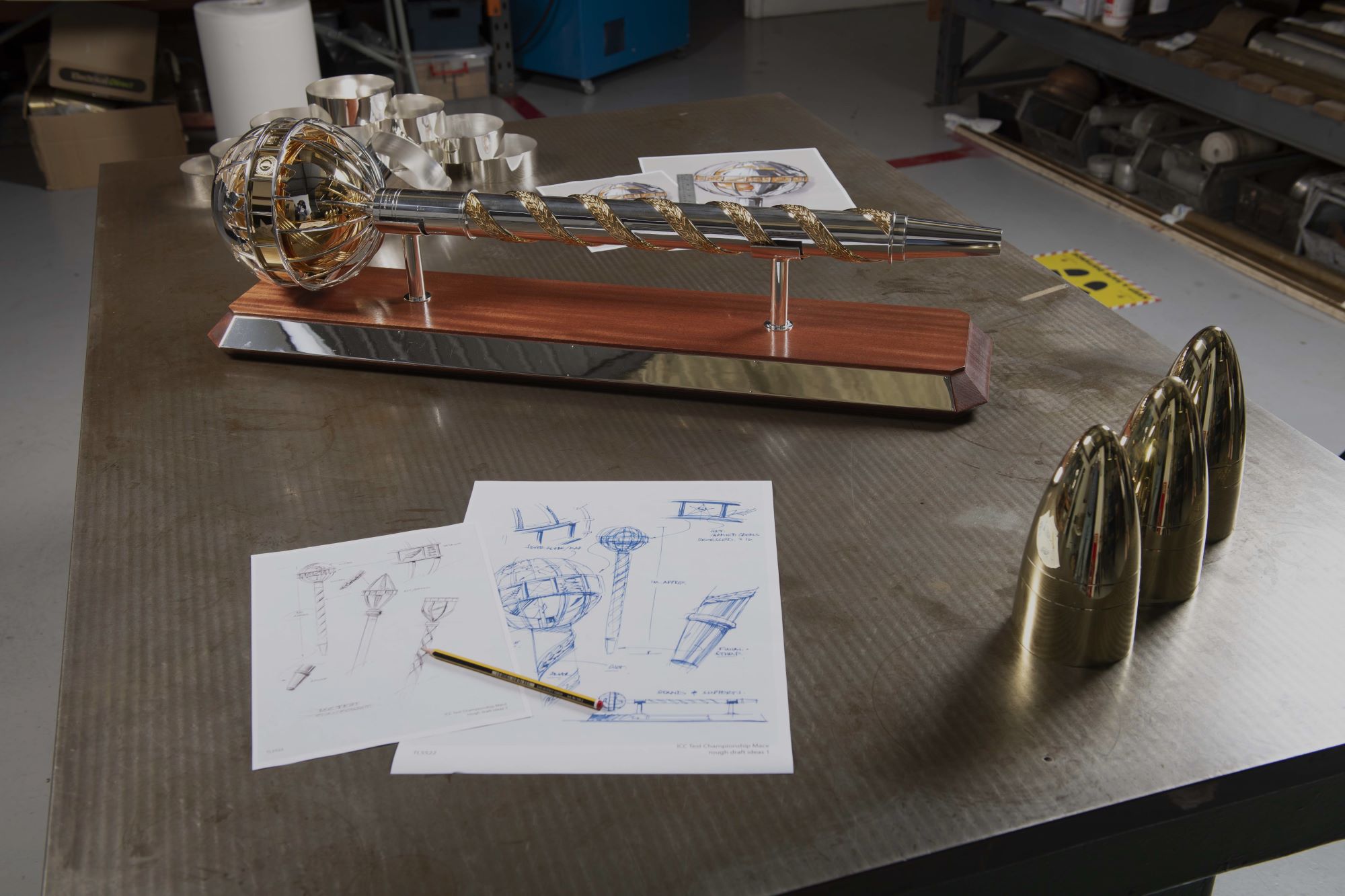

Starting in 2001/02, the original mace was awarded by the ICC to the top ranked Test nation on 1 April each year, alongside a cash prize of $1m. It resided primarily in Australia, with the country holding the mace nine times in its first 15 years.

Now, as Australia once again prepare to do battle for one of global cricket’s most prestigious prizes against South Africa at Lord’s, Brown describes the thought process that went into designing the mace almost 25 years ago.

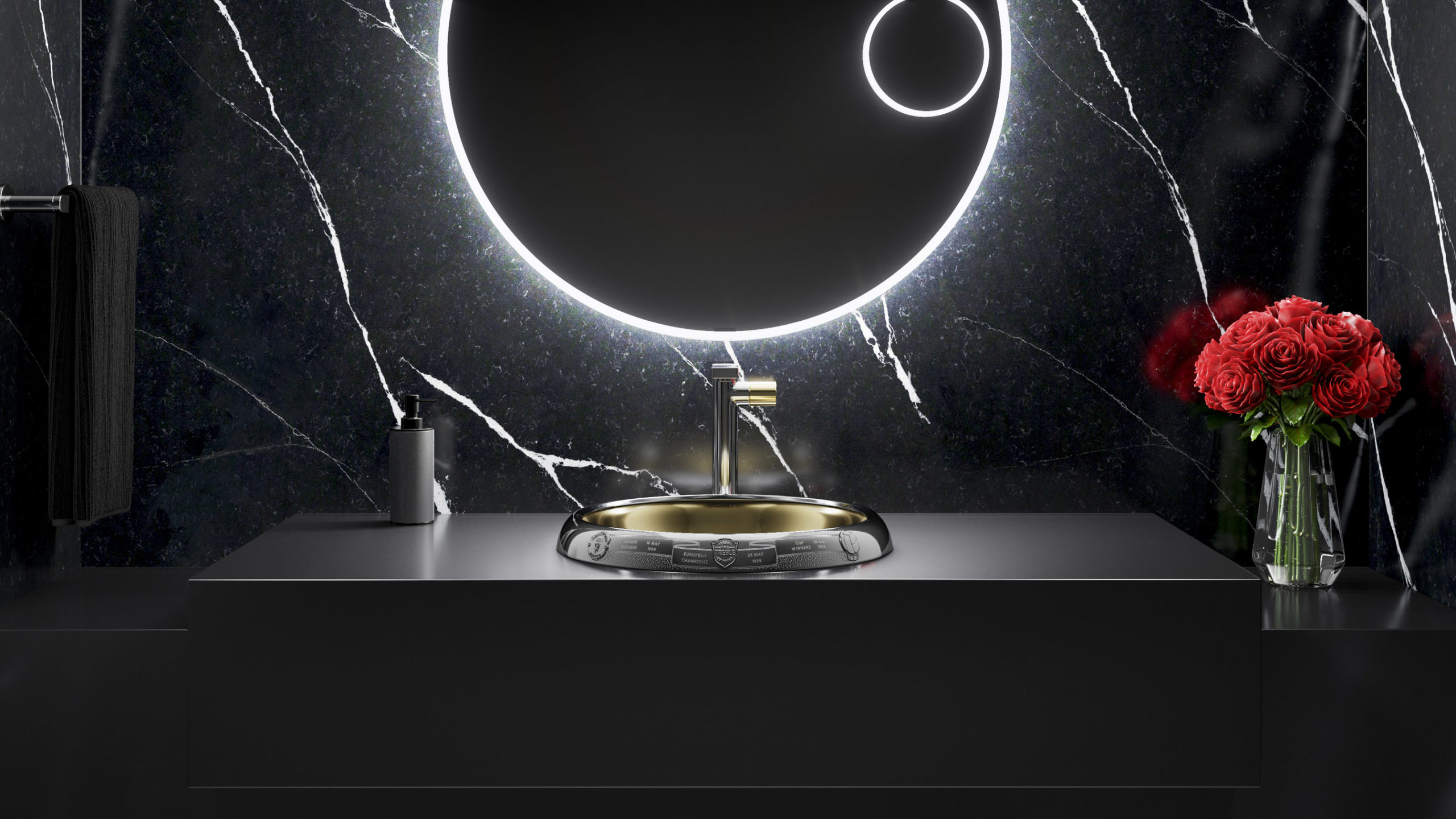

“There’s also the idea that a mace is a ceremonial object – and as the mace is presented at the World Test Championship Final, a touch of ceremony about the presentation would be a good thing too,” he says.

“It’s such a different sporting format and event so it really does need a visually different trophy. I saw the presentation as a moment of great pride for the winning captain, his squad and support team to enjoy – followed by moments of reflection on just how hard it is to win.”

![baton of hope mike mccarthy recieves baton from Thomas Lyte]() A Symbol of Hope for the UK

A Symbol of Hope for the UK![Designers Makers Of The Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Processional Cross 3 1306x1800]() Culture Round-Up: 2022 and the Queen Elizabeth II Processional Cross

Culture Round-Up: 2022 and the Queen Elizabeth II Processional Cross